Article & photos by Damon Crain

Modernism Magazine

Volume 10, No. 3, Fall, 2007

Blenko is an ideal example of the boundless innovation of mid-20th century America and the purest expression of a uniquely American modernist glass art. The best of Blenko's work demonstrates a direct connection to the revolutionary principles of the time in both art and design, be it evidence of a Henry Moore and Russel Wright-like sensibility in the work of Blenko's first designer Winslow Anderson; the influence of Paul Klee or Le Corbusier in the work of Blenko's second designer, Wayne Husted; or the kinship of Blenko's third designer, Joel Myers, with Richard Diebenkorn's sense of color and Eero Saarinen's mod organic forms. Undoubtedly, this accounts for Blenko's appeal to collectors of all things modern.

The significance of Blenko's contributions to American design and studio glass, especially its core innovations of dramatically enlarged scale and bold solid colors, has remained largely unrecognized by museums, academics and texts. While experts have cited 1960s Pop Art as the precursor for the enlarged scale that is seen as an innovation brought to glass by of the Studio Glass movement, Blenko had been developing oversize pieces since at least 1954. In addition, Blenko pioneered a market for affordable modern art glass by putting pieces of exceptional design and quality within economic reach of the largest segment of the population - the bourgeoning middle class - helping to pave the way for the many independent glass studios that followed. The story of Blenko's ascent is the one of a company determined to reinvent itself in order to succeed during hard times and savvy enough to ride the wave of America 's post-war years. |

|

Above: Early Blenko vase in Ruby, c. 1930's. 5.25"h x 5"d. |

The company's founder, William J. Blenko, was born in 1854 to a poor family in London . Through formal training and apprenticeship, he developed superior skills as a chemist and specialized in the formulation of colors for hand blown sheet glass used in stained glass windows. Blenko immigrated to the U.S. in 1893 to escape from England 's oppressive class system and to pursue America 's promise of economic opportunity by founding his own glass company. His first three businesses were short lived, but undeterred, he easily found employment at other glasshouses in order to replenish his finances. Such was the quality of his work as a chemist and foreman that, while working at an Ohio glass factory in 1919, he received a job offer from Tiffany; instead, in December 1921, he founded the Eureka Art Glass Company (renamed The Blenko Glass Company in August 1930) in Milton, West Virginia . |

|

Above: This Blenko Heavy Swedish Type vase #R497) in Sea Green with Crystal coil, is attributed to Carl Erickson. Designed c. 1940, it was shown in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's 1950 Exhibition "Twentieth Century Glass: American and European." 10"h. x 6.25d.

|

Two important innovations set the company on a solid footing early on. The first was Blenko's invention of a new process for producing larger sheets of hand blown glass more efficiently. The second was the perfection, in 1924, of the holy grail of stained glass: a formula for a ruby-hued glass whose color would not be altered by re-heating. This formula joined the nearly 300 others that Blenko had developed. By 1927, thanks to the combination of a good product and the sales acumen of William Blenko's son Bill, the company was successfully selling handmade colored sheet glass to American artisans and studios. Only two years later, however, the economic crisis that sparked the Great Depression destroyed the market for stained glass, as construction of new buildings came grinding to a halt. Undaunted, Bill Blenko managed to persuade his reticent father to diversify and try producing tableware using the same material they had been using for sheet glass. Bill approached Carbone & Sons, a Boston retailer and importer of fine Italian and Swedish glassware, with an offer to supply them with a competitive domestically made product. This was a brash proposition; Blenko had never before made tableware. |

Above: Winslow Anderson, large four-dent vase #910-4

in Chartreuse, designed 1948, 7.5" h x 5.5"dia |

|

Above: John Nickerson, Vase (#7220S) in Turquoise, designed in 1972. 12.5"h x 4"d. This vase presages Nickerson's independent Studio Glass work for which he has since acheived much fame. The vase began as a bottle form, and was then cut on a bias. Such cold work was uncommon for Blenko, beacuse of the added expense of production |

Carbone's finest glassware was produced by Giulio Radi of Arte Vetrario Muranese (A.VE.M) with whom Carbone had contracted to reproduce the famous designs of Italian masters like Barovier and MVM Capellin. This was to be a steep learning curve indeed for Blenko.

The brothers Louis Miller and Axel Muller, who had been trained at the Kosta factory in Sweden where their father was a master glassblower, were swiftly hired by Blenko from the nearby Huntington Tumbler Co. The two most enduringly important regions of glass production in the 20th century were Italy and Scandinavia, both noted for their groundbreaking design sensibility and incomparably skilled craftsmanship; in America, they converged at Blenko. |

|

Above: Wayne Husted, Vase (#5942L) in Persian, designed in 1959. 15.5"h x 3.75"d. Signed. Shown in the exhibition "Glass 1959" at the Corning Museum of Glass

|

Blenko's early tableware line of simple, classic and utilitarian shapes quickly became its primary product. As has been the case for the company's entire history, the glassware was handmade, mouth blown and hot-worked with shaping tools in the traditional off-hand manner. Needing to train most of the workers from scratch, Blenko did not try to compete with the Italians on technical perfection. Rather, the company turned to its greatest strength: the huge variety of stunning and vibrant colors that it had developed over the past decade for stained glass. These colors became the most recognizable attribute of Blenko's tableware. By the mid 1930s, Blenko's glassware had earned an enviable reputation and could be found for sale at such leading stores as Macy's and Gimbel's in New York, Lazarus in Ohio and Neiman Marcus in Texas. A new Scandinavian influence came to Blenko in 1937, in the form of a new Swedish foreman, Carl Erickson, whose father and grandfather were master glassblowers at the Reijmyre factory in Sweden . After adding some noteworthy designs to Blenko's line, marketed as "Swedish Type," Erickson left in 1942 to start his own company, the highly regarded Erickson Glassworks. His departure highlighted Blenko's need for design direction, but the war years would put a hold on any new developments. |

|

Above: Wayne Husted "Architectural Scale" three-part Epergne (#5832) in Charcoal, designed in 1958. 35"h x 11"d. Signed. The traditional epergne is a dining table centerpiece for presenting fruit, desserts or flowers. Husted's version, made of three individual pieces og glass nestled inside one another, exemplifies how he transformed well established objects into entirely new and sculptural forms. |

After the war, urged by their sales representative Ed Rubel, Blenko decided to distinguish itself from its competitors by embracing modern forms and made the pivotal decision, in 1947, to hire its first design director, Winslow Anderson. Anderson, a graduate of Alfred University - renowned for its ceramics program - was handpicked for this coveted job by his teachers there. This move put Blenko at the vanguard of American companies at a time when the profession of "designer" was in its infancy.

An artist and designer, Anderson was deeply influenced by the abstract painter Hans Hoffman, and the art theory he espoused in his book "Search for the Real," as well as by Bauhaus philosophy and Scandinavian design. Anderson also had the distinct advantage of being steeped in the New York art scene while stationed in Queens during the war. His mixed media artwork was even exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim (then the Museum of Non-Objective Art ) in 1944 alongside that of distinguished artists such as Harry Bertoia and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. |

|

| Above: Joel Philip Myers, Decanter (#6732L) in Plum, designed in 1967. 29.5"h x 4.25"d. |

At Blenko, Anderson was given free rein to develop an entirely new line. In fact, Bill Blenko left for Europe on Anderson 's first day without so much as leaving instructions. The resulting line of about 30 new tableware designs, including vases, glasses, bottles, decanters, plates, bowls and pitchers, had a fresh new look. Along with their minimal, organic and graceful shapes, Anderson also took the important step of introducing a daring new greenish yellow color called "Chartreuse" to the repertoire of more standard colors like amber, amethyst, emerald, ruby and turquoise. Buoyed by the color's unqualified success, Blenko established the introduction of dramatic and unusual new colors as a cornerstone of its identity.

Anderson's most profound contribution was to gently challenge the rational expectation that designs be primarily functional. He created forms so refined and refreshing that their function seemed to be no more than a fringe benefit to the object's sculptural qualities. In 1952, after aggressive attempts to lure him by both Steuben Glass and Raymond Loewy, Anderson left for Lenox China . His departure was a significant blow to Blenko; there was no doubt that the company's strong growth and success were largely due to his intuitive knowledge of glass and his exceptional designs. |

The "Rialto" Specialty Line was one of three very adventurous lines Wayne Husted designed in 1960. These lines, both technically and aesthetically different from the company's standard line, indicate an impulse to innovate and experiment in spite of the risks. The Specialty Lines are a testament to a company in its prime. Rialto 's translucent white was achieved by adding tin to the batch, which had the unfortunate side effect of making the glass much more brittle. Combined with the annealing differential with the applied Ruby elements the loss rate was very high during manufacture and after. Very few were made as hardly any were ordered - a as result the Specialty Lines were a financial disaster for Blenko, almost forcing them into closure.

Left to right: #15-TO vase, 9.5in.H, #2-TO decanter, 18.5in.H, #1-TO decanter, 25.75in. #13-TO vase, 13.125in.H, #16-TO hurricane 8.5in.H on top of #8-TO candleholder, 6.75in.H, #4-TO decanter, 14.25in.H, #3-TO decanter, 17in.Hm #12-TO vase, 8.5in.H |

|

Above: John Nickerson "Charisma" Specialty Line Vase (#7221X) in Crystal with Ruby, designed in 1972. 17.25"h x 3.75"d. "Charisma" was the first Specialty Line Blenko had attempted since 1961. With its Ruby garland color suspended in Crystal, the line refined a 19th-century American glass production technique from the mid-Atlantic region. |

Not coincidentally, Anderson 's tenure also marked the beginning of the inclusion of Blenko pieces into a new type of museum show then proliferating around the country. These influential and popular juried exhibitions promoting modern design were organized by museums convinced of the need for arbiters of good taste for the masses at a time of unparalleled cultural development. Retailing then in the range of $3-$25 (about $25-130 in today's dollars) Blenko glass was luxury good for the middle-class and a prime candidate for these exhibitions. Blenko's products were included in the "etroit Institute of the Arts "An Exhibition for Modern Living" in 1949 and the Museum of Modern Art 's popular semi-annual "Good Design" shows from 1950 through 1954. Blenko's critical success is easy to explain: quite simply, no other American glass company was producing new, modern shapes in hand-blown glass at this time. Blenko had the market cornered.

In 1953, Wayne Husted, Blenko's bold new designer, also fresh from Alfred University , arrived with a single-minded fervor and vision. The door that Anderson had nudged open, Husted blew away entirely. For Husted, vessels were no more than a pretense for creating abstract, sculptural shapes. A 1958 New York Times article entitled "Glass Objects Reflect Trend to Art in Home Today" demonstrated the sculptural qualities of Husted's work by featuring his Blenko designs alongside Venini glass by Fulvio Bianconi. |

Above: Joel Philip Myers, cone-footed vases, designed in 1970. From left to right: #7041 in Olive Green. 12.5"h; #7042 in Tangerine. 12.75"h; #7043S in Turquoise. 14"h; #7043L in Surf Green. 14.25"h.

|

|

Above: Hockaday Associates, blenko ad, 1961, incorporating Wayne Husted designs

|

Husted also took an active role in marketing. He turned Blenko's catalogues into seductive photographic sales tools with his own Paul Klee-influenced artwork on the covers. He also convinced the company to invest in ad campaigns for which he selected Hockaday Associates, one of the most influential agencies of the day. Husted was a keen interpreter of market demands; with a creativity that knew no limitations he would seize on seemingly minor trends or suggestions and transform them into an entirely new genre. Blenko's California sales reps notoriously always wanted items "a little bigger;" Husted's brash retort was the inception of the "architectural scale" genre, designs suitable for displaying only on the floor as free-standing sculpture, ranging from 26 to 38 inches tall.

Blenko's third designer, Joel Philip Myers, arrived in 1963. Myers's aesthetic was already quite sophisticated; he had worked with Donald Deskey in New York and Richard Kjaergaard, an influential ceramist, in Denmark . Myers was aware of the nascent Studio Glass movement and quickly set about learning glass blowing himself. Effectively maintaining an independent practice as a glass artist while at Blenko, Myers became an early and active participant in the Studio Glass movement. By his own account, allowed Myers to see the possibility of his own career as a studio glass artist while designing for the factory. "Blenko has permitted me complete creative freedom and has encouraged me to experiment," he said. "My experimental work contributes many ideas and directions for use in our regular line.There is no reason to think that working for industry compromises a craftsman's aesthetic values." |

|

Above: Blenko ad designed by Joel Philip Myers, 1967showing Myers designs from that year |

At Blenko, Myers clearly reveled in the 1960s psychedelic re-interpretation of the Art Nouveau aesthetic, with masterfully exaggerated organic vessel forms. "I permit the glass to sag, flop, flow, stop, start, stretch," he said. "I control and yet am being dictated to by the glass.." Myers introduced some of Blenko's best gaffers to the possibility of artistic creation and, as a result, a few, including Shorty Finley and Earl Carpenter, developed noteworthy renown in their own right. This immediate connection between Blenko and the Studio Glass movement only deepened during Myers' fruitful tenure.

Myers's later, very influential studio work belies an undeniable interest in color that was surely nurtured by his involvement with Blenko. In evaluating his contemporary work, critics regularly cite color as a primary concern, but ascribe this narrowly to an interest in artists such as Henri Matisse and Mark Rothko, as if unaware of his eight-year tenure at a glasshouse whose founding concern was color.

Myers began exhibiting his own glass while at Blenko, including at the Toledo Glass National II in 1968 alongside glass masters Fritz Dreisbach, Dominick Labino, Marvin Lipofsky and Richard Marquis and at the Smithsonian Institution's "Ceramic Arts USA" in 1966, an invitational exhibition featuring leading American artists, where he showed with Labino. Myers introduced Lipofsky to Blenko in 1968 and Dreisbach in 1976. (A sculpture that Lipofsky made at Blenko in 1968 is now in the collection of the Smithsonian's Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum.) Myers's inclusion in the seminal 1969 exhibition "Objects USA" is testament to the importance of Blenko not only to the Studio Glass movement but to the larger Craft Movement as well. Myers left Blenko to establish the glass department at Illinois State University and today ranks as one of the most recognized and exhibited glass artists in the world.

|

|

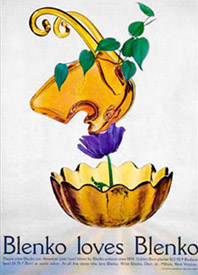

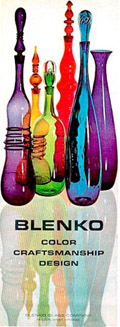

Blenko Catalog cover

by Wayne Husted, 1955

|

Blenko's success and relevance did not by any means go unnoticed by the guardians of high culture. Museums were actively exhibiting and acquiring Blenko for their permanent collections as early as the 1940s. The most prescient and revealing of these museum exhibitions was the 1950 show "Twentieth Century American and European Glass" at the Metropolitan Museum . In this exhibition, Blenko appears alongside Tiffany representing "outstanding examples" of glass design. The catalogue commented that developments in design and production had helped lift the glassmaking industry "from its lethargic traditionalism. On one hand mechanization of the industry has created unequaled standards of precision and quality in production, while on the other the original designs of able artists have given it uncommon distinction."

Blenko appeared again at the Metropolitan Museum in the exhibition "Craftsmanship in America" in 1952, but perhaps the most significant exhibition to include Blenko at this time was the groundbreaking "Glass 1959," a juried international world-wide survey of the glass industry at the Corning Museum of Glass. Blenko's entry was an exceptional design: a cylindrical vase with u-cut top and weighted encased crystal base, designed expressly for the show by Wayne Husted. Its presence alongside the likes of internationally esteemed houses Salviati, Venini, Kosta and Orrefors lent Blenko important exposure and prestige. More recently, the Corning Museum included Blenko in a small but powerful survey exhibition entitled "Decades in Glass: the '50s." |

|

| Above: Wayne Husted "Accents,: designed in 1958, both in Tangerine. #5730L, 10"h, left, and #5730, 7.75"h, right. |

Blenko's golden period ended as a result of two developments: the death in 1969 of Bill Blenko, the company's guiding force, spelled the demise of Blenko's early vision, and the Studio Glass movement began to challenge the company's standing in the marketplace of unusual, modern hand blown sculptural vessels. Direct competition with studio glass production - unique glass objects by independent artists in small studios - though certainly a factor was less of a problem than the small glass factories that the movement inspired.

Unbeknownst to Blenko, its fourth designer, John Nickerson, hired in 1971 and the first to arrive well versed in studio glass, heralded the impact of the emerging Studio Glass movement. Ironically, Nickerson's designs generally shunned the more flamboyant Studio Glass influence in favor of a simpler, more restrained aesthetic, with a renewed focus on the functional vessel form. No doubt this was in part due to the new president, William H. Blenko Jr., grandson of the founder who called for new priorities for a new time. He imposed a more commercial standard, with more conservative colors and simpler designs that could be executed efficiently with less handcraft skill. At the same time, work by Studio Glass artists and small companies inspired by or founded by Studio Glass artists, was becoming more mature and accessible. After only four years' tenure, Nickerson left Blenko to cultivate his own successful independent Studio Glass practice, participating in numerous exhibitions including the Corning Museum 's "New Glass '79." |

|

| Blenko's success stemmed from its progressive attitude, its fearless young designers and, of course, high quality, handmade glass never before seen in such large-scale, fantastical shapes or bold colors, of an importance not seen since Tiffany's domination of American Art Nouveau glass. In a 40 year period of fostering dramatic new aesthetic developments and pioneering design, Blenko built a market for and a national awareness of modern art glass: sculptures for the domestic environment. |

Above: all Joel Philip Myers designs |