The Stockholm Manifesto

Rebuilding the framework for symbolic object making.

| adapted from a lecture presented in Octber 2023 at the |

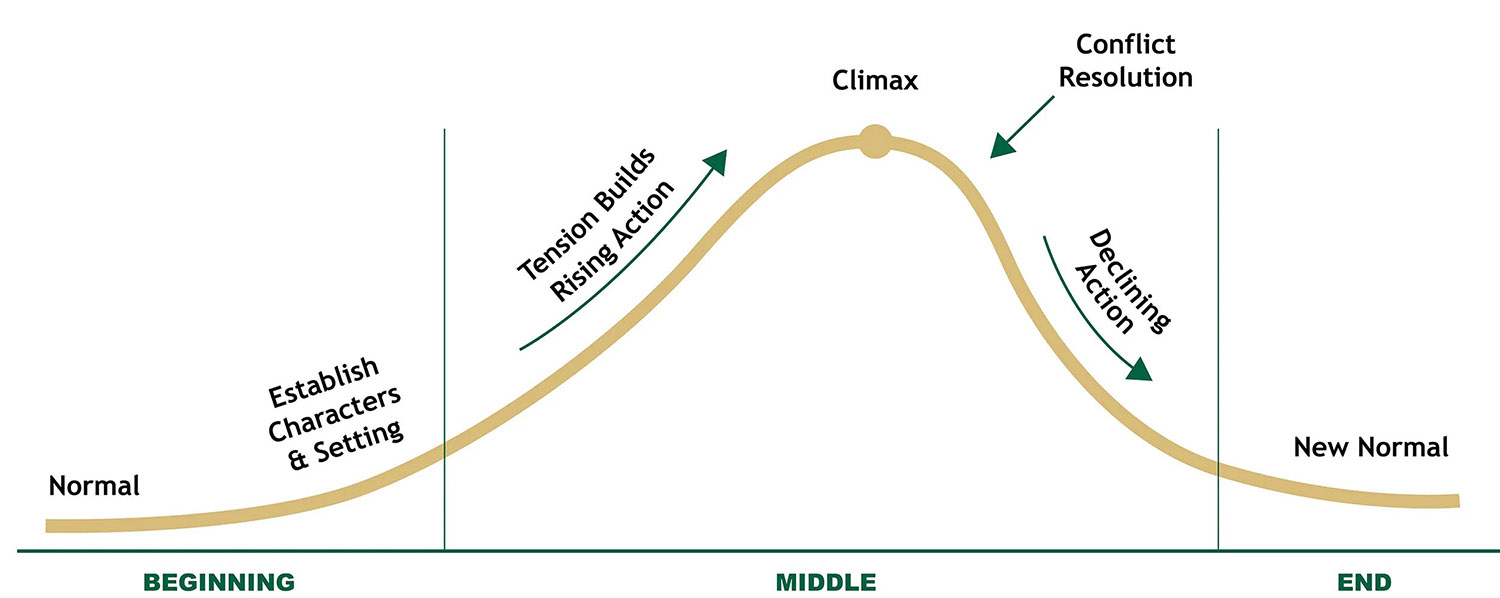

We create our world with stories. Storytelling is our innate activity. Our dual hemisphere brain structure indicates how fundamental this process is; one side talking to the other, back and forth. This internal voice, an inescapable and unending private conversation with ourselves, is how we resolve our messy thoughts and contradictions. Our stories are the stitching together of ideas to create context, to create a foundation for new ideas. It is our primary tool for making order out of chaos. My story is a quest to understand and to channel the powers of a cultural force that temps me with its seemingly magical possibilities. It is the force that we conjure when we engage in the making and interpreting of symbolic objects, stories encapsulated in physical form. These activities are as unavoidable to us as our inner voice; our minds and our hands are restless tools as we think and move through a world made of matter. Where once we merely whittled away the hours, or made a stitch in time, we now build satellites and particle colliders. How fortunate we are, to be alive at this moment in history, to be playing the roles we are playing at this point in the story that we have been collectively building for eons. This moment offers us incredible opportunity. It is a moment of unprecedented connectivity, exchange, and coordination. We have been operating in a world fragmented by distance, language, and different cultural perspectives - but now, to a degree never before possible, we may choose to come together, through technology and travel, to promote a shared vision and tell a story of who we wish to be. |

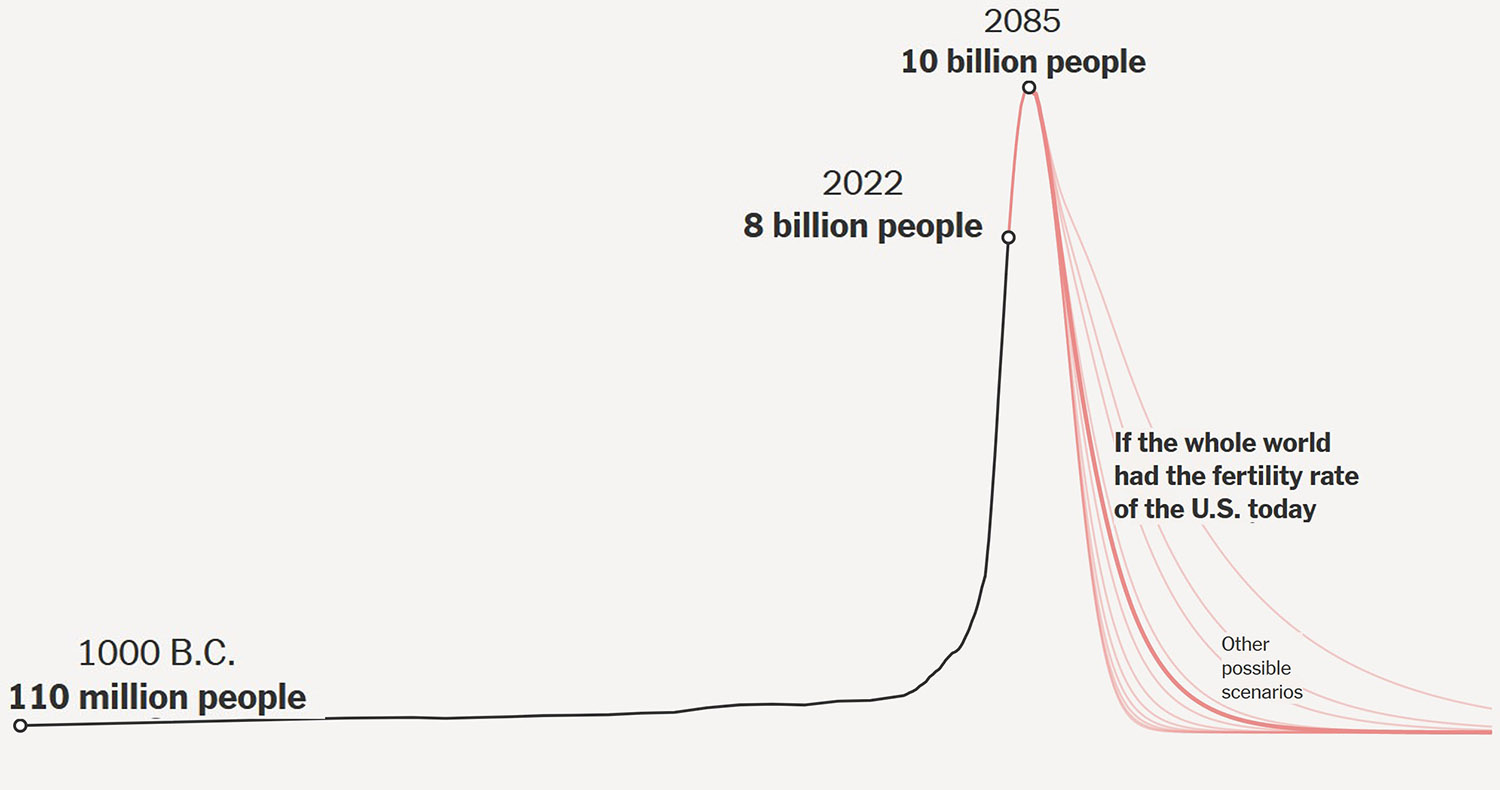

In the 1950’s, a dawning awareness that our actions could cause untold destruction to the climate and global ecosystem crept up on us, but we dithered and denied to our detriment. Now, a freshly hopeful realization beckons; the limits to growth are at the horizon. Experts have begun to warn that the global human population is likely to peak sometime around 2085, and then plumet as it rounds a sharp bell curve. This revelation gives me deep existential relief and brings powerful new context to the work that we do to prepare for the future. We now find ourselves at a crucial juncture. Our task is to form an alliance to fend off the agents of chaos whose work risks ruining us before we can secure a fortress of human potential, and shine from it a beacon for all of humanity. The actions we take now, will determine what the other side of the bell curve will look like; it can be a dystopia of diminishing opportunity and regression, or it can be an existence of plentiful resources and widespread equality, managed with the tools and systems that we build today. It is the dreamers and the storytellers, who have the power to inspire, and to plant the ideas of who we can become and how. If you are reading this, you are a dreamer. Our success begins with broadly agreeing on a shared framework, built with potent, foundational words that we choose to imbue with simple, clear, and undisputed meaning. Are there three related words more slippery than art, craft, and design? Their edges are so vague and blurry as to threaten to render them meaningless. It’s curious that such large and important fields of human endeavor have proven maddeningly difficult to define consistently, that their meaning lacks popular consensus on what they refer to. Until now, this flux has been more a feature than a failing, as the flexibility allowed for experimentation and development. This flexibility fueled growth, but with the increased scale and complexity of these fields, we have now reached a point of diminishing returns. The endeavor is at risk if we do not take a new tact |

At the inception of my business twenty years ago, I struggled to figure out how I could best make a constructive contribution to the cultural dialogue. I was aware that a long-developing cultural shift in our understanding of art, craft, and design, was gaining momentum - and I wanted to play a role in furthering it. The challenge was, that while the meaning of these words had become freshly fluid for the few involved in the dialogue, they meant something quaintly specific to anyone outside of it. Many people understand art, craft and design based on a matrix of criteria; materials, processes, where the activity occurs, where the resulting work is shown, and each one’s different relationship to physical functionality. The words are also often understood in relation to each other, particularly in the sense that “this is not that”. That pragmatic approach is not a bad start, but the devil is in the details. While I have described it in the abstract, those who function with that approach typically define it in the very specific. For example: art is paintings, made in a studio, by a painter, who shows work at a gallery, and sells it to museums. While that might seem to be a significant oversimplification, to a great many people it is a good working definition of most art - and that is a tragedy because it locks away access to so much powerful potential. Initially, I feared that if I engaged these three words in my own endeavors, that I would distract from, or undermine, my goal of demonstrating that art can transgress the categories of craft and design - in fact, all categories of cultural production. I thought that if I called my gallery something suitably ambiguous but simple, like Culture Object, and explicitly didn’t use the word “gallery”, I could short-circuit people’s expectations by avoiding associating myself too closely with any one of them. I believed that, with a slight of hand, I could sidestep the debate about the boundaries and contours of these three words – I could be all of them at once. I was wrong. It turned out that lack of guidance didn’t sidestep the problem of people’s expectations, it only absolved me of responsibility for helping people understand the work I was presenting. The resulting ambiguity proved too uncomfortable and confusing for most people. Be it stars in the sky, or lines on the road, we do best with well-defined points of reference. Context is everything. Now I’m navigating an impending name change so that I may better achieve my vision, and I can’t help but wonder, what else did I get wrong? Looking at my beliefs with fresh eyes, earned through action, I can see that I unnecessarily clung to the idea that art was a thing that looked a certain way. The path forward requires the sacrifice of some sacred cows. Our task is to discover a fresh understanding of art, to see that it incorporates process and many modes of presentation, including craft and design, but it is also more than that. If we are to lead others, and put signs on this road to discovery, we must unify to clarify our words and reframe our work for a broad audience by adding depth and fresh relevance to our understanding of what art IS and what it DOES. Much time and effort must be sunk for such a profound change to be felt on a broad enough cultural level to be effective. It is generational work, but we are already well into it. |

Since the industrial revolution, we have broadly categorized creative production into three streams of specialization: skilled craftsmanship, industrial design, and fine art. Balkanization is a strategy for analysis and efficiency. While it has helped us in both respects, it has also fostered a harmful popular misperception that these fields are mutually exclusive co-equals. By putting forth rational and clarified definitions of these words, we can empower ourselves with a strong foundation for our work, so that we may more effectively reach the world. CRAFT is a verb, meaning to produce something with skill and care. Its use as a noun is of limited value as it applies only to a small range of work whose primary purpose is development and demonstration of skill, process, and technique. Function has no bearing on craft beyond education of methods of production. DESIGN is the practice of producing objects that serve a physical utility, it is judged by its ability to serve its function. Aesthetic concerns are applied to design only as secondary aspects. Craft and design are foundational concepts that require simple definitions, art requires something more expansive. Whereas reality is the perception and interpretation of matter, ART is the manipulation of reality by the collective transmogrification of meaning using a talisman. Art combines craft - the physical manipulation of matter - with a conceptual framework for building a shared reality based on belief, meaning, representation and interpretation of ideas in physical form. Art engages the uneasy truth that reality is perception and demonstrates our control of that perception. The beauty of it is that there is no need in art, only want, we engage with it voluntarily. Art is creation, the realization of desire and hope in material form. Art is a system for asking and answering a two-part question; what do we want and why? It is our construct and our context. Like money, art only has value because we agree it has value. Like religion, art is only meaningful if we believe it is. Art’s value is as a powerful shared fiction. |

At the heart of our very nature is to want meaning and purpose, with art, we create it. The work that is produced by the practice of art is a locus for our energy on collective, inter-generational storytelling that shapes who we become as a culture whether we individually believe it or not. With this understanding, which is now over a hundred years in development and well tested, we achieve an important new stage in the project we call ‘Art’. It is no longer confined to being embodied in a limited manner of specialized format. Art is set free! We know this now, all that is left is to leverage the potential it unleashes. We begin by broadcasting and normalizing this new paradigm. Our tradition, when art slips its old skin and no longer appears as we expect, is to call it Impressionism, Pointillism, Fauvism, Dada, Suprematism, Futurism, Surrealism, Art Brut, Action Painting, Color Field, Installation Art, Environmental Art, Performance Art, Pattern & Decoration, Productionism, and Relational Aesthetics. This is our historical strategy for growing our schema; by grafting a new branch on to it. With thanks to Rosalind Krauss, I call our present endeavor Expanded Field Art. |

|

|

The strategy to deliver this idea to a broader public, outside of the art world, has been emerging over a period of decades by engaging the more familiar and foundational fields of craft and design. This approach has evolved simultaneously in multiple locations and in different media. From within the artworld, artist like Richard Artschwager, Donald Judd, Jessica Stockholder, and Jorge Pardo broke down barriers politely. From without, innumerable Studio Craft Movement artists and conceptual designers nibbled at the edges. The change has been so broad and incremental, the transgressions so radical and fundamental, that it has escaped detection as a cohesive development. |

|

|

The prophet of this new vision of art, is the critic and philosopher Arthur Danto. The inflection point that made it visible was the year 1997 with the publication of his seminal book “After the End of Art”. Danto’s revelation began in the 1960’s when he observed a narrative that manifested itself between the work of Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol. I interpret this narrative as having reached an apotheosis in the Productionism movement of the 1990’s. |

|

|

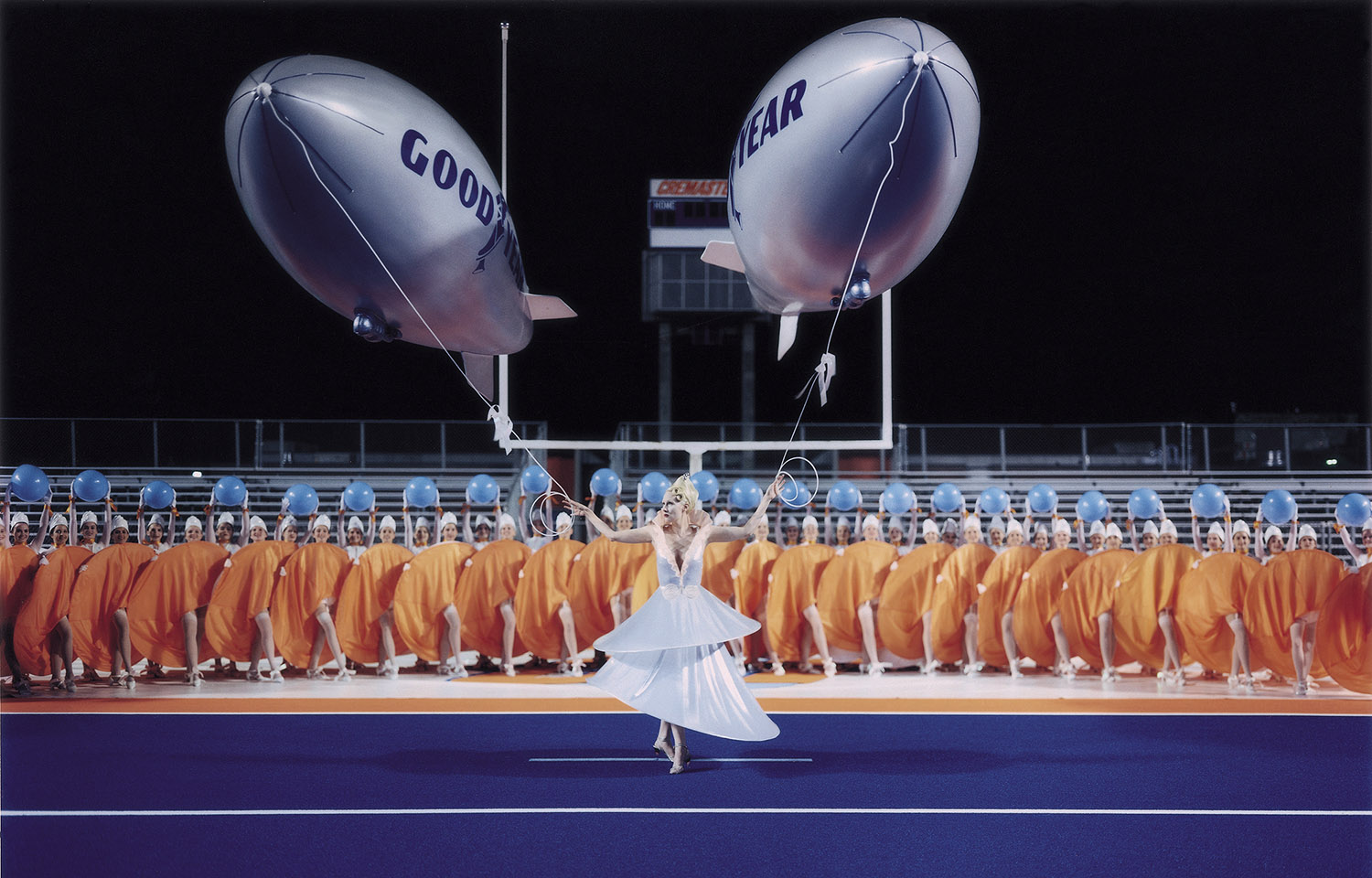

Productionism is an elaborate directorial take on art practice. It represented a transition, facilitated by Post Modern theory, which effectively rendered all historical styles and ways of working equally legitimate. The artist-made, the ready-made, the assistant-made and the fabricated; all equal. The painting, the photograph, the performance; all equal. Their equality allowed them to be integrated. Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle is the intersection of theater + craft. Jeff Koons’ entire oeuvre is design + craft. Their work is pointedly produced under the banner of art, which it is also. Productionism represents the culmination of an enduring drive to reunite what we have repeatedly broken down into discreet pursuits. |

|

|

In the new millennium, the prior decade’s developments offered a toehold for the traditionally "craft" aligned materials of glass and ceramics to find fresh purchase in the upper echelons of the art world. Josiah McElheny’s glass figures, and Sterling Ruby’s Oldenburg-esque ceramic ashtray appeared in the Whitney Biennial in 2000 and 2014 respectively. |

|

|

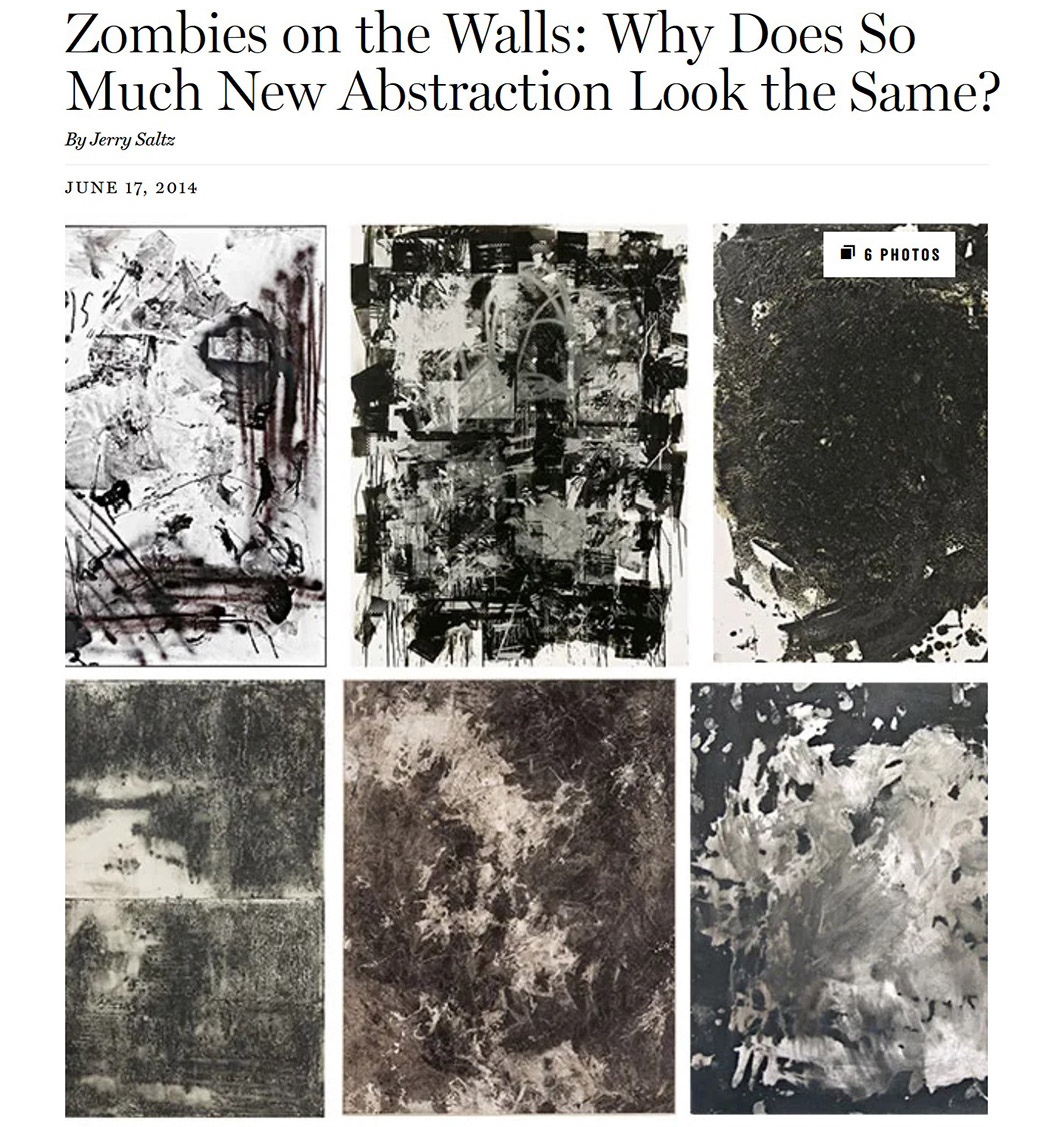

Contemporaneously, the narrative of design-as-art, which had revealed itself previously only in small ways to small audiences, found surer footing in rich commercial ground, through salesmen like Simon DePury with his Design-Art auctions, and Larry Gagosian who introduced Marc Newson as one of the first designers to be represented by a major art gallery. Danto’s conception of the narrative arc of modern art was further validated by the vamping art of the aughts that resulted in the humorously derogatory term “Zombie Formalism”. Such work is characterized by the aping and mythologizing of past styles. I contend that it is also an example of Warhol’s vision of ‘business art’, art as representation of art as a financial instrument. This conveniently appealed to the wall street class that flooded the art market with unprecedented money in the aughts, fueling the trend. This is the context we find ourselves in now. It is an impoverished one, wherein the public dialogue about art is both fractured and bloated. The endless parade of art fairs and galas provide party filled backdrops for celebrities and the super-rich, but no one speaks of relevance or makes a case for what art can do for us. Art’s dominant drive has become the market itself, ruled by a handful of international mega-galleries. It’s like an elaborately coiffed animal locked in a cage, chewing at itself. |

At first glance, it might seem ironic then, that this is where I insert myself in the story, as a person selling art, proposing to course-correct art away from the market, and back to ideas. My quest is for relevance, and if art is about the market, then selling art is a market about the market – and there is no relevance to be found in an echo chamber. Now, once again, we must clarify words. Let me make a clear distinction about my role: I am not a curator, and I don’t curate exhibitions, I organize them. I’m a dealer – and I’m particularly amused by how that word is also associated with cards and gambling. As a dealer, I put forward my sincere judgement, and the knowledge used to achieve it. I gamble my business that I will be believed. Credibility is my currency. If I misrepresent myself, if I present myself in a manner that contradicts or undermines the logic of my beliefs, I fail. A dealer is building and selling fresh history, cultivating new story lines, and enabling artists to expound upon them for the duration of a shared relationship. Selling art is a pragmatic means to fantastical ends. I shepherd sympathetic new work into existence and find homes for it to ensure its survival, and the spread of its ideas. How is this different from being a curator? Curators are bound by an institution and its politics, selecting from work that has already emerged and established, to contextualize it within a space that they do not control. Where a dealer shapes and promotes, a curator reveals and informs. Dealers build up and sharpen, curators peel back and soften. I have enormous respect for curators, so I reserve the term for a person with a degree in art history or curatorial studies, or who is employed at a non-profit institution with the purpose of selecting and presenting objects in a non-commercial venue to the public for educational purposes. Certainly, their actions have great potential to impact the market, but as an unavoidable byproduct, not as a goal. The superficial commonality between a curator and a dealer, is that they both exhibit artists’ work. The deeper commonality is that they each support and interpret art for the benefit of a larger audience, but at different stages and to different, if overlapping, audiences. |

|

|

As a dealer, my 'program' is my mantra and my mission; it encapsulates my foundational beliefs and my agenda. It is the direct heir to Arthur Danto’s central contention that the project of modern art was answering the question "what can art be?". While Danto’s answer proved the Duchampian dream that art can be anything, that art is defined by context and consensus, my program rests on the observation that the oblique lesson is the importance of controlling the context and creating consensus. Context is everything because everything is relative. That is the launching point for the work I do. My program seeks to answer the question "what can art do?" by concentrating on objects that integrate conceptual and functional roles. I champion work that embodies a respect for function by virtue of its skillful manufacture, and by engaging technical innovation and material exploration. I look for work that is executed in service of narrative exposition that leverages engagement with historical dialogues and classical themes, as seen through the lens of contemporary relevance. |

Organizing commercial exhibitions is the heart of my work. As with anything I do professionally, I begin with the question "how can this help me tell my story and make people want to engage with it?" I’m proselytizing my program; everything is in service to this function. When I organize exhibitions, I am engaging an ecosystem: the ideas – expressed through the program, the people – to transmit the ideas to, the work – as a vehicle for the ideas, and finally, the presentation – the arena where it all comes together. |

|

|

Because context is everything, presentation is paramount. Not only in the physical realm, but in the psychology of experience. Presentation may be the last piece of the puzzle, but like a keystone and not a flourish. I’ve taken great risks with my presentation - perhaps too many, and perhaps too big, but half-measures are never an option when your work requires conviction. Knowing that risk and change come at the cost of the headwinds of inertia, I have fought a signature battle related to presentation - and I’ve fought it fiercely. |

|

|

|

|

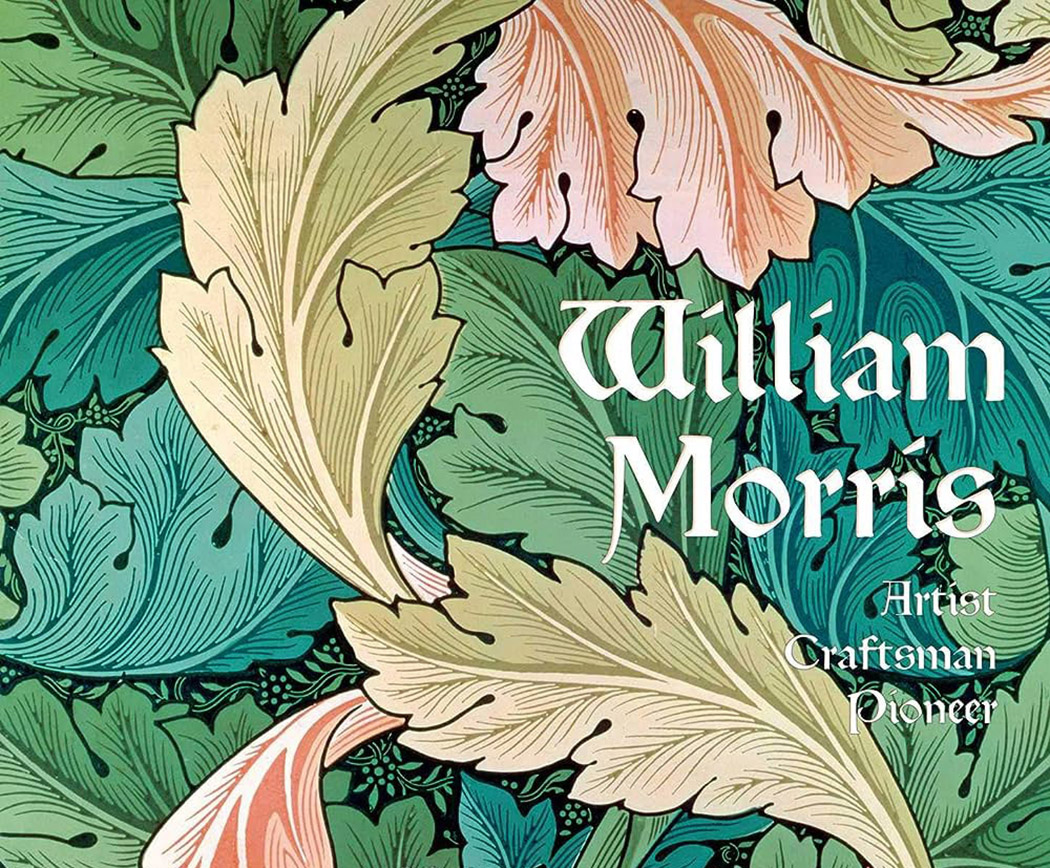

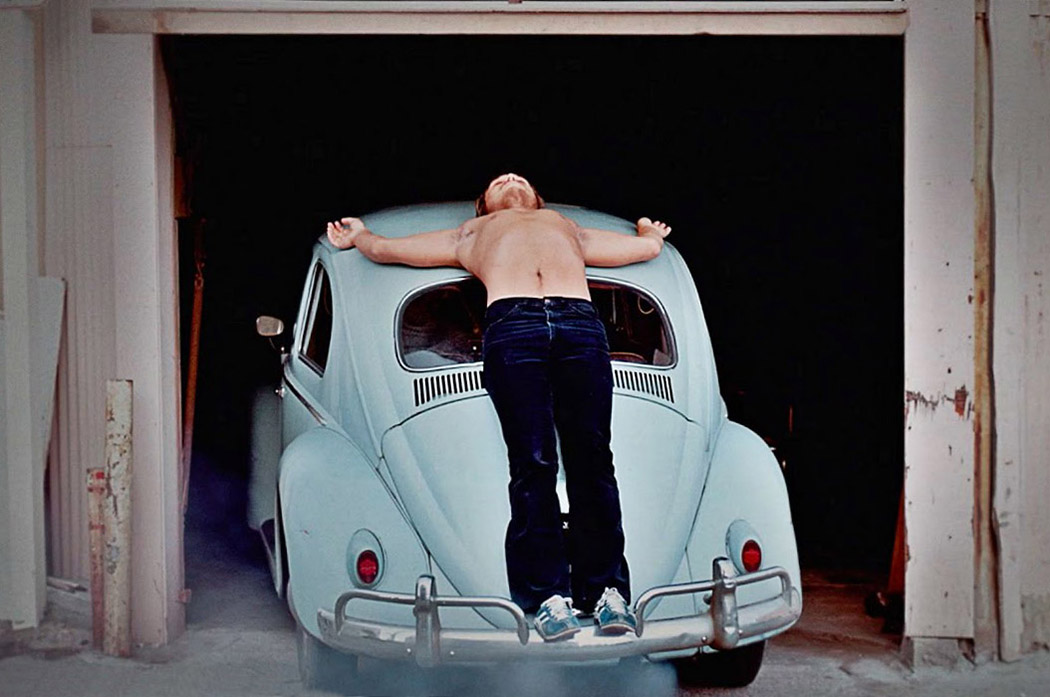

The beast I seek to slay is the white box. It is art’s equivalent to the Quantum dilemma of Schrodinger's cat: If you seal art in a white box, then aim at it a beam of focused attention, is it dead or is it alive? If context is everything, and you negate context by using a stand-in for nothingness, how can the work be alive? Can it then only live in that context? The answer is maybe and sometimes. The inevitable next question is, why would you take that risk? Convention and convenience is the uninspiring realpolitik answer. The white box format was developed to shelter the freshly experimental modern art of the mid-20th century. When art no longer looked like landscape paintings or busts, and interiors were perhaps a bit fussier, we needed exhibition spaces for art where one would not bleed into the other. Now that we have grown beyond that, and especially with art in functional form, I would like to put that unnecessary genie back in the bottle. The primary exhibition room in my gallery was the velvet walled Peacock Room, a salon-style exhibition room that rewinds to mimic the type of domestic space that art was primarily exhibited in prior to the professionalization and institutionalization of galleries in mid-20th century. It is inspired by the famous Aesthetic Movement Peacock Room, now at the Smithsonian Museum, created in 1877 for the London townhouse of art patron Frederick Leyland by leading interior designer Thomas Jeckyll. The American painter James McNeill Whistler was hired to paint the room with a gold decorative motif designed by Jeckyll. |

|

|

The room was a dining room, but also intended as an exhibition space for Leyland’s Quing Dynasty porcelain collection. After taking significantly too many liberties with Jeckyll’s design, Whistler was fired. He then retaliated by illicitly painting on the walls a mural of two peacocks fighting, representing the artist and the collector. He titled the piece "Art and Money; or, the Story of the Room". That struck me as an excellent ready-made historical context of great depth. My Peacock Room was designed to feature typologies of furniture that are typically focal points in a room; the credenza, the bar or cabinet on stand, the center hall table, and the console. The furniture was commissioned by me from my artists, and it would either be part of the exhibition on view, or it would act as pedestals for the exhibition work. In practice, it has proved complicated for casual visitors to grasp, and its inflexibility for temporary exhibitions has been challenging. |

In response, I recently I executed a small renovation to transform the front room into a hybrid box-like exhibition space with layout and plinths proportional to a domestic space. The Peacock Room is now for non-exhibition presentation of work. It remains crucially important to me that the primary frame of reference for the work I show is the domestic environment, yet, in a commercial context I have discovered I need to help visitors focus on the work and not the presentation. The details of how to best manifest these ideas remains in flux as the story evolves. It is with great pleasure that I say the horizon ahead is broad, and new adventure awaits as we chase a narrative that infuses a new understanding of the freshly enlarged power and potential of art when it is aligned with craft, design, and more. I leave you with a quote from the field of Quantum Physics, from the theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli’s book "Reality is Not What it Seems".

- Damon Crain |